ADVERTISEMENT:

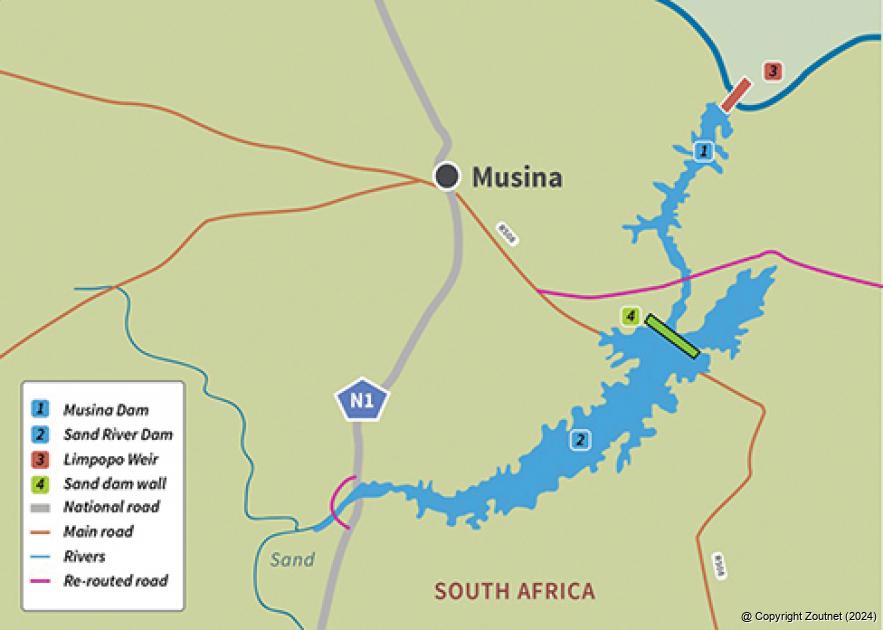

A weir across the Limpopo River and two new dams, the Musina Dam and Sand River Dam, are proposed to supply 90% of the water needed for the highly controversial MMSEZ north of the Soutpansberg. Image from the Water Governance of the Northern Limpopo report.

Developers propose massive dams to feed MMSEZ monster

The findings of a second research report dealing with the water requirements of the proposed Musina Makhado Special Economic Zone (MMSEZ) was recently made available during a virtual media launch on 12 August. The report once again highlights the fact that the MMSEZ developers refuse to acknowledge that just not enough water is available in the area to support a project of this magnitude.

The report, entitled Water Governance of the Northern Limpopo, was compiled by Dr Victor Munnik from the Society Work and Politics (SWOP) Institute from the University of the Witwatersrand. This is the second research report regarding the issue compiled by Munnik, the first being the Water risk of fossil fuel mega projects in Limpopo: the MCWAP and the MMSEZ report published in May 2020. Both reports were commissioned by the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung’s SA office, a social democratic foundation that aims to strengthen the forces of democracy and strive for a just, sustainable, democratic economic system.

Munnik was tasked to investigate the governance of water in die Limpopo River catchment area, both on the South African side in which the MMSEZ will fall, and the other riparian countries, namely Zimbabwe, Botswana and Mozambique.

The scope of the second research report was recently extended to include analysis of a pre-feasibility study that became available in April this year for the proposed ‘Musina Dam’ and ‘Sand River Dam’ to store Limpopo River floodwaters. The report looks at how feasible this dam and other dam options are and whether such a megaproject could be financed while the curtain is falling on coal development in light of climate change.

“What we are dealing with here is a late coal-based megaproject in a closed catchment,” says Munnik. This means that all available water is already allocated or, in some instances, over-allocated. This fact, Munnik says, the developers of the MMSEZ refuse to acknowledge.

According to Munnik, the MMSEZ project is a late coal-based project, taking into account that the date set to do away with all coal-power industries globally is 2050 to try and reduce the disastrous impact of climate change. “So, it is basically Limpopo politicians and the superpower of China trying to slip in one last big coal megaproject,” says Munnik. He contends that this project defies climate change and the lack of water in the closed catchment area.

Water remains the biggest issue

The issue of water availability for the project has been a contentious one from the start. One of the biggest objections to the project is the mystery as to where its water supply will come from. The proposed Musina and Sand River Dams are the latest proposal from proponents of the MMSEZ, seeking to supply more than 90% of the water needed for the minerals complex (to include a coal-fired power station and various steel and related industries).

According to the pre-feasibility study, the first of the dams, the Musina Dam, will be built just downstream from Beitbridge and just before the site where the Sand River runs into the Limpopo River. The second dam, the Sand River Dam, will be built higher up in the Sand River itself (see accompanying map).

The plan is to first construct a weir across the Limpopo River where the Sand River joins it, which is planned to take up to 60% of the Limpopo’s total flow, leaving 40% for ecological requirements downstream. They will then pump the water from the weir to a settling dam and from there to the Musina and Sand River Dam. Pumps will need 130MW and 208 MW of power to pump the water into the two dams, from where it still needs to be pumped 50km south to the MMSEZ.

The Musina dam wall will be 45m high and 488m long across the Sand River, yielding 13Mm³ of water per annum without Limpopo water and 57Mm³ of water per annum with Limpopo water. The dam’s life span is a projected 12 years and if a silt filter is installed (which is not included in the developers’ budget), 25 years. The Sand River dam (of which two versions have been planned) will be constructed five to eight kilometres from the Limpopo and the dam wall will be either 63m high and 1 158m long, or 80m high and 2 600m long. As a result of the dam wall, 4 000ha will be flooded and the N1 will have to be rerouted. A bridge will also have to be built across the R508. At least eight to 10 years will pass before the water from these dams will become available, with the proposed MMSEZ needing a full 80Mm³ of water per annum to function within 10 years. “So, there is every possibility that timelines will be crossed. The MMSEZ will either be without water, or will take water from other users,” says Munnik.

No conceptual design

Regarding the proposed dams, Munnik says that no conceptual design of the dam(s) and associated infrastructure exists in the pre-feasibility study. “Therefore, it is not possible to arrive at a possible investment cost for this project. There is no on-site geotechnical investigation for the recommended dams and weir sites, meaning that there could be unanticipated difficulties for construction, which may affect costing and construction time,” says Munnik.

According to Munnik the pre-feasibility report also does not sufficiently address options for institutional agreements such as permission from Botswana, Zimbabwe and Mozambique. “In short, it has not done any negotiations with the other riparian states. There are also no reports of negotiations with prospective investors such as municipalities, the Department of Water Affairs and Sanitation or Lepelle Northern Water to consider integration with existing water supply infrastructure in the area,” says Munnik.

Cost cannot be calculated

With so much uncertainty, Munnik says, the most likely cost given in the pre-feasibility report of R14,50 per m³ will rather be R16,17 per m3 with the addition of the energy cost. This is expensive water. “But we have no reason to believe that these figures will be correct, because we all know that the cost o megaprojects can escalate beyond control and [become] unaffordable. This could tempt the developers to turn to other water sources and, in doing so, put pressure on other water users,” warns Munnik.

As stated, Munnik’s research report focuses on issues regarding the proper governance of water resources. “In the absence of proper water governance, strange ideas [such as those proposed above] are coming into being,” says Munnik. This is where a catchment-management agency (CMA) can play a critical role.

Munnik says that the objectors to the proposed MMSEZ have defended very important things, such as the livelihoods of locals outside the formal economy, biodiversity, and water resources, from the start. “It is important to remember that the majority of people in Limpopo are water users whose water requirements are so small that they are often not properly counted, and their formal rights not protected. They can be easily infringed upon,” says Munnik.

Citizens have rights

Regarding citizens’ water rights, Munnik says that many people have basically forgotten what the National Water Act of 1998 says, namely that water belongs to the citizens of South Africa and that the government is the custodian. “It is like we are the owners and government the management. They should actually be reporting to us what is happening to the water and whom they are giving water to through the licensing system. However, it was really noticeable in the previous research and this research how absent Water Affairs is in this whole question. We don’t know if there is a license application. We don’t know! There is no comment and there is definitely no leadership from the department to say what is possible, what is dangerous, what is allowed and so on. There has just been an absence,” says Munnik.

CMAs can play major role

Munnik highlights the fact that the Water Act makes provision for participatory, integrated water-resource management in the form of CMAs in decentralised catchment areas. These are agencies comprised of local water users in specific areas who take control of what happens to their water by means of a decentralised water board. The original idea of the Act in 1998 was to have 21 CMAs in the 21 water-management areas in the country. Sadly, due to no proper support from the government, this idea never really gained momentum. “It is a bit of a sad story. Only two of the 21 CMAs came into being and started operating,” says Munnik.

Munnik’s research shows that CMAs can be quite agile in dealing with water issues. They are, however, facing many obstacles. “For more than 20 years there has been a reluctant rollout of CMAs,” says Munnik. This, in some instances, is due to fear of job losses by the very same government officials entrusted to establish these CMAs, believing that the CMAs will take over their duties. “Our main political players are also not that comfortable with the idea of decentralisation,” says Munnik, adding that, for example, every time a new water minister is appointed, the new minister must be convinced of the validity of CMAs. Treasury has also since reduced the number of CMAs to six, from the original 21.

With the reduction of CMAs to six, the Limpopo and Olifants catchment areas have merged into a super-CMA. As a super-CMA, Munnik says, the Limpopo CMA could become a major player in deciding how water is used and allocated. A number of urgent issues need to be addressed by the Limpopo CMA, and Munnik encourages people to engage with these processes as they happen and to really explore their potential in improving water governance through CMAs. He stresses that rivers need to be protected, for example through environmental-flow regulations. “Climate change is already changing conditions in the Limpopo water-management area, and will continue to intensify. Participatory water governance in the South African section of the international Limpopo basis can provide a powerful encouragement to similar developments in other Limpopo riparian countries and increase international co-operation, as the IUCMA has done in Mozambique,” says Munnik. He concludes by saying that actively rolling out CMAs would be a good opportunity for the Department of Water Affairs to reinvigorate its role as the custodian of water resources in South Africa and to practically support the participation of voices that have so far been drowned out by stronger actors with many more resources at their disposal, such as those pushing the MMSEZ agenda.

The complete report will be made available as soon as a printable format is ready.

News - Date: 28 August 2021

Recent Articles

-

From sportscaster to advocate

21 April 2024 By Silas Nduvheni -

New lab welcomed by Bungeni learners

20 April 2024 By Thembi Siaga -

Rialivhuwa and Sally are king and queen

20 April 2024 By Kaizer Nengovhela -

'Headman demolished my house'

20 April 2024 By Kaizer Nengovhela

Search for a story:

ADVERTISEMENT

Andries van Zyl

Andries joined the Zoutpansberger and Limpopo Mirror in April 1993 as a darkroom assistant. Within a couple of months he moved over to the production side of the newspaper and eventually doubled as a reporter. In 1995 he left the newspaper group and travelled overseas for a couple of months. In 1996, Andries rejoined the Zoutpansberger as a reporter. In August 2002, he was appointed as News Editor of the Zoutpansberger, a position he holds until today.

Email: [email protected]

ADVERTISEMENT: